This post is based on a talk about a paper published at the 2020 ACM CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2020). The full research paper by Richmond Wong, Vera Khovanskaya, Sarah Fox, Nick Merrill, and Phoebe Sengers “Infrastructural Speculations: Tactics for Designing and Interrogating Lifeworlds ” can be found here: [Official ACM Version] [Open Access Pre-Print Version]

In our paper, we ask how speculative design can be used to more explicitly center and raise questions about the broader social, technical, and political worlds in which speculative artifacts exist. To do so, we draw connections between speculative design and infrastructure studies, which offers a set of lenses to help ask questions about ongoing relationships and practices needed to maintain and support systems. We present a set of design tactics to help speculative design researchers make use of the analytical lenses from infrastructure studies.

The HCI community has taken up practices of speculation, such as critical design, speculative design, and design fiction to interrogate emerging technologies. In these techniques. Researchers design conceptual artifacts and experiences to evoke alternative sociotechnical worlds, to explore the possibility of different social values, norms, behaviors, and material configurations.

These practices often focus on creating a speculative product or artifact. For instance, in prior work by several of the authors, we created fictional products including a workplace smart toilet that tracks menstrual cycles and other health information. This is shown in a fictional product catalog, allowing the view to easily think about questions related directly to use. What might it be like if you had to use or interact with this product?

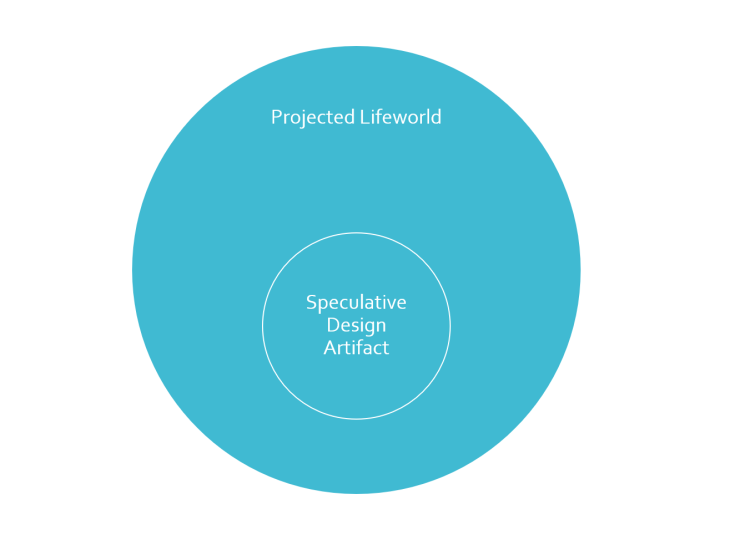

While presenting a speculative product, like a fictional smart toilet, foregrounds questions of direct use (left), we might also be interested in questions that concern practices in the artifact’s “background” (right)

However, other types of questions that we might want to ask remain more implicit, particularly those not about immediate use. For example, how does this impact janitorial and custodial labor needed to maintain the smart toilet? What differential experiences might arise from its long-term use? What regulatory frameworks may emerge around new types of data collection? These questions may not be readily apparent just through the presentation of a speculative artifact, as they happen in the artifact’s “background.”

As designers increasingly use modes of speculation to interrogate questions of broad, societal concern—such as climate change, the role of big tech in political radicalization, and widening income inequalities—there is a need to adapt the speculative design toolbox to include approaches that explicitly focus beyond immediate moments of use, to explore the broad and disparate impacts of technologies as well as the maintenance and repair labor required to keep them working. While an inquisitive designer or viewer might come to these questions on their own, we want to provide some scaffolding for designers who wish to explicitly consider these types of questions through their speculative designs.

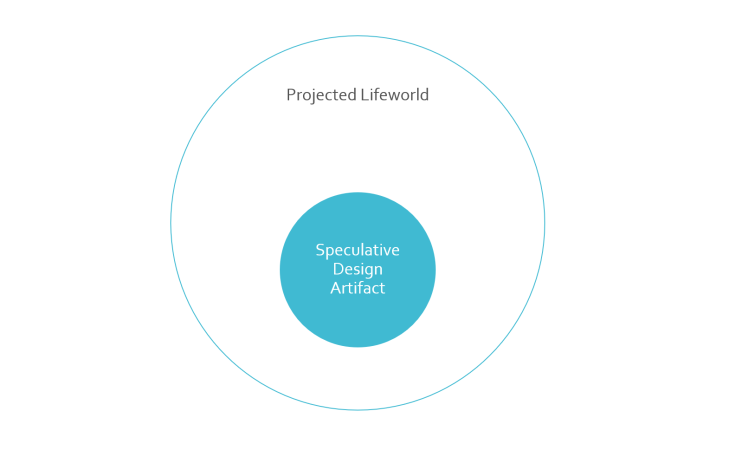

Projected Lifeworlds

An artifact and its projected lifeworld

To help us shape our approach, we use the concept of lifeworlds. In philosophy, anthropology, and in some prior HCI literature, lifeworlds are used to refer to the social contexts and experiences that a user has. We build on this, presenting the idea of projected lifeworlds, or the things that must be true, common-sense and taken-for-granted in order for the design to work. In speculative design, the lifeworlds of a potential future or alternative world are projected by a design artifact. However, we find that these projected lifeworlds are often implicit. Attention is often drawn most immediately to the speculative design artifact in the foreground, leaving the lifeworld implicit in the background.

How can we help “fill in” the projected lifeworld?

However, one might be interested in exploring issues that occur in a speculative product’s lifeworld, beyond the artifact and its immediate use. This requires shifting our analytical lens to think about and “fill in” projected lifeworlds more explicitly. We turn to literature from infrastructure studies to help us make this shift in our focus.

Infrastructure Studies

Indeed, HCI’s study of technologies has broadened beyond the immediate user-system relationship. Beyond questions of immediate use, HCI researchers have also begun to examine practices of ongoing maintenance and repair labor, technology policy issues, and political and economic conditions. One set of analytical lenses that scholars have drawn on to ask these questions includes research from science and technology studies on infrastructures.

Briefly, infrastructures are sociotechnical. They include technological components, as well as the social institutions and practices that make them durable, such as standards-setting, maintenance, and repair. Infrastructures support particular forms of human actions while complicating others. For example, the electrical grid is built using technologies like power plants, substations, and dams. It relies on social institutions such as power companies and regulatory agencies that shape and maintain it. Yet, people’s access to, and experience of electrical power is variable. Infrastructures might seem hidden from view, seemingly operating in the background. However, we can see and understand these infrastructures, if we shape our analytical lenses to help bring these arrangements and practices to the forefront.

We reflect on the idea that speculative design is already concerned with infrastructural questions. However these concerns tend to remain implicit, as we often focus on depicting the artifact, and leave the lifeworlds of the artifact implicit. Using insights from infrastructure studies and reviewing existing speculative design work, we present a set of design tactics to help design researchers bring lifeworlds into more explicit focus.

Design Tactics for Infrastructural Speculations

The paper presents eight design tactics for creating infrastructural speculations

In the paper, we describe eight design tactics for creating infrastructural speculations. These tactics aim to help designers consciously and purposefully place and reflect on the role of infrastructures in their speculative work. Each tactic is grounded in a particular insight from infrastructure studies. Each tactic helps to bring a different aspect of the artifact’s lifeworld into focus. I’ll highlight 3 of these today.

Tactic: Place the same speculative artifact in multiple lifeworlds.

First is “placing the same speculative artifact in multiple lifeworlds.” This builds on the concept of “infrastructural inversion,” an analytical move to foreground the relationships among people, practices, artifacts, and institutions that normally exist in the background of a situation or activity. Similarly, speculative designs can be crafted in ways to emphasize the importance of the background lifeworld as being just as, if not more, important than the speculative artifact itself.

In deploying this tactic, the design researcher takes a single artifact and articulates multiple lifeworlds in which that artifact might make sense. For example, Pierce’s collages of smart products re-deploy existing consumer IoT cameras in ways that suggest alternative lifeworlds, beyond what is depicted in advertising and marketing materials. Pierce uses metaphors of lamps and curtains to speculate lifeworlds where IoT cameras have physical on/off switches, curtain shades, and used like interior lamps for decorative and mood-setting purposes. One can look at these re-deployments to ask what other lifeworlds might make sense for the IoT camera. One might be a lifeworld where IoT cameras are used decoratively and aesthetically like lighting today. Another might be a lifeworld where people adopt, but mistrust their devices. Here, they might use add-ons that subvert surveillance, such as lens covers, on/off switches, and wireless jammers.

This tactic de-centers the speculative artifact as the main unit of analysis, and instead brings our attention to the importance of the lifeworld. By explicitly portraying multiple alternative lifeworlds, design researchers can interrogate how the social meaning of a technology is co-constructed between the artifact and its lifeworld. The diversity of lifeworlds depicted through this tactic also sheds light on the multiplicity of the present reality. Within the world that we inhabit, technologies exist in multiple contexts and may have multiple social meanings.

Tactic: Depict stakeholders beyond users, and relationships beyond use

A second tactic is to “Focus lifeworld descriptions on stakeholders beyond users, and relationships beyond use.” This builds on infrastructures research that focuses on the practices required to support sociotechnical systems, such as maintaining, repairing, managing, selling, regulating, or dismantling systems. This connects with existing HCI design work that looks at other types of relationships between humans and systems beyond that of “use.”

This tactic then, focuses on “uses beyond use.” For example, Stead’s Toaster for Life design fiction presents a speculative networked toaster with sustainable attributes, including the ability to repair, upgrade, customize, recycle, and track component parts. The fiction foregrounds a set of relationships and practices with the toaster that go beyond use. The toaster’s modularity centers repair and maintenance practices as a key mode of interacting with the toaster. The fiction also points to a broader set of stakeholders who interact with the toaster through practices of recycling, fabrication, and tracking of the toaster’s components throughout its lifecycle.

This tactic can be used to explore such questions around the multifaceted relationships and practices related to speculative artifacts. What forms of work might be necessary to maintain and sustain a system across time? Who does this work, and how is it valued?

Tactic: Focus on the bureaucratic mundane — artifacts or organizations representing larger systems of power

The last design tactic I’ll discuss is to “Create mundane artifacts or organizations whose disturbing effects are due to the systems of power and institutions within which they are embedded.” This comes from an understanding that new technologies are deployed in relation to existing institutions and systems of power.

This tactic contrasts with speculative exercises designing intentionally “evil” technologies. Rather than the “evilness” of a technology coming from malicious intent of its designers, the “evilness” arises from the systems of power in which the technology is embedded or adopted.

For instance, a design fiction from my dissertation work depicts an organization, rather than a product. The organizational fiction depicts UX designers at a company, InnerCube. They attempt to surface and address problematic social values related to a harmful use of their platform. But they are stymied by their company management’s desire to not lose a contract with a particular client. They are later are replaced by Anchorton contractors or “ethics strikebreakers” who do the problematic work instead. The negative outcomes from this scenario do not directly arise from a designer’s evil intent, nor from a problematic technical system. Rather, the negative outcomes stem from the organization’s arrangement of power and the encompassing structures of financial reward.

This tactic calls attention to systems of power and inequality of the past and present. It calls on us as design researchers to grapple with how those systems might persist in the futures we imagine. Notably, this tactic is not about creating grand futuristic dystopias. Instead, it seeks to recognize the current and past dystopias that people face in their everyday lives, surface the systems of power that (re)create those dystopias, and imagine how those might be (re)configured in the future. This tactic examines how infrastructures enable or constrain action in ways that can at first seem subtle, but cause enduring, large-scale effects. This helps a design researcher explore how through forms of institutional power, technologies can constrain or shape action in uneven ways. What are the seemingly mundane practices of people embedded in organizations responsible for creating or maintaining technical systems? What are the effects of those actions, particularly if they lead to harmful outcomes?

Discussion

Each of the infrastructural speculation design tactics helps foreground a different aspect of a projected lifeworld. Together the tactics we present provide strategies for thinking beyond initial moments of design and use. They open up a broader set of stakeholders, practices, institutions, and related systems for speculative inquiry. The tactics help shift our focus from immediate uses of artifacts to the broader lifeworlds in which they sit. By making different aspects of the lifeworlds more explicit, the tactics help can designers shift how they see a speculative artifact and its relation to the lifeworld. I’ll highlight two of these shifts here.

Types of analytical shifts the design tactics can help us make

First, we can shift from thinking about whether a system is working or broken, to looking at ongoing relations and practices surrounding a system. Infrastructures are never universally working or broken on their own. Rather, infrastructures may work for some but not for others. Labor and work are required to make an infrastructure function at a local level. The design tactics draw attention to the relations and practices surrounding technical artifacts: How might a technical artifact work partially for some, but not for others? What practices and relationships might be necessary for a system to function?

Second, the focus on everyday practices means that we can think about the multiple ways people relate to technologies in both beneficial and harmful ways. People encounter technologies in the mundanity of everyday life and new technologies get adopted and appropriated by and into existing institutions and systems of power. This is different that dystopian speculations of the future, which tend to flatten experiences – everyone has a similar harmful experience. Moreover, dystopic speculations have been critiqued by scholars such as Oliviera& Martins, Sondergaard & Hansen, and Tonkinwise, for hiding questions of race, class, and gender; and for pushing societal harms into an imagined future, not recognizing how people in the present already experience injustice and suffering. Rather than erasing differences, infrastructural speculations draw attention to differences and the imaginaries, institutions, and power structures that support and enforce them.

While speculative designs imply a lifeworld surrounding a speculative artifact, infrastructural speculations re-focus design researchers’ explicit attention to the careful crafting and analysis of the lifeworld itself. Drawing on concepts of infrastructures, the design tactics we present offer a variety of strategies for re-focusing attention on the lifeworlds that tend to operate in the “background” of speculative design. This brings into focus practices and relationships beyond use; multiplicity of experiences; and the longstanding power that infrastructural systems have to classify, sort, and affect human experiences. Infrastructural speculations are of pertinent importance as designers increasingly use modes of speculation to interrogate questions of broad societal concern, beyond moments of immediate invention and design, and beyond moments of individuals’ use.

Paper Citation:

Richmond Y. Wong, Vera Khovanskaya, Sarah E. Fox, Nick Merrill, and Phoebe Sengers. 2020. Infrastructural Speculations: Tactics for Designing and Interrogating Lifeworlds. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376515