When I use my computer in my room, I often hook it up to my Samsung SyncMaster B2230 Monitor. I purchased it from Amazon.com a few years ago, but besides that, I don’t know where it came from. Time to being investigating!

The monitor I use every day – but I have no idea where it comes from beyond Amazon.com

My goal was to find out more about how the technology was made – where, what factories, what materials, and more. My first thought was to look at the product description on the Samsung website. I didn’t find much here – although it did say that my monitor is ENERGY STAR(R) compliant, and EPEAT(R) Silver Standard, meaning that they are engineered or produced in ways that are at least partially environmentally friendly, or use less power. While that was good to know, it didn’t give me specifics.

I then turned to the corporate Samsung pages, and found a page about global procurement – there was some information on how to apply to become a supplier in Samsung’s global production chain, and information on business ethics, but it still didn’t give me the specifics I needed.

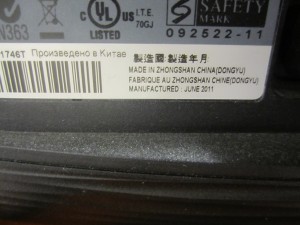

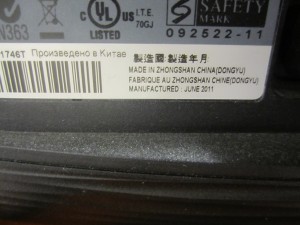

I turned to look at the monitor physically. Not finding anything about its production on the box, I turned to the back of the monitor, finding the ubiquitous “Made in China” label.

The label on the back of the monitor

Indeed it was made in China, in a place called Zhongshan. This gave me a few clues. I figured I try looking at the Chinese version of the Samsung site, and did a few Google searches, eventually finding a listing of sites from their global network. I found that in Zhongshan, there’s a factory or company which is a production subsidiary of Samsung called China Printed Board Assembly. This in turn is a part of Tianjin Samsung Electronics Display Co. Ltd., which created circuit boards, printed board assembly machines, and millions of monitors. Beyond that, it was very hard to find specific information about the company. There were some possible maps of these sites, but the map pins didn’t seem too accurate. Even though I know the name of the subsidiary company or factory where my monitor was probably made, I don’t really know much else. There were several sites that listed the companies as subsidiaries of Samsung. There were some phone numbers to these companies in some of the official Samsung documents, and I suppose given enough time, and someone to translate Chinese, I would be able to dig deeper into this.

From here, I couldn’t follow the path any further back – it would have been a great opportunity if I had been able to get all the way down the supply chain to the actual resources, metals , and plastics used in the making of the monitor. Though I would imagine after its manufacturing, it would go on a ship across the Pacific to the west cost, where it would be shipped by truck or railroad to an Amazon warehouse, who then ship it to me when I order it.

In general, supply chains are very much blackboxed – whether it is concerning the origins and manufacturing of hamburger meat, my clothing, or my monitor. By using subsidiaries, or contracting with various suppliers, as it seems that Samsung and many other companies do, the information becomes more disparate and harder to find. In one sense, this is a complication of increasing globalized supply chains, but in another sense it makes it easier for businesses to lessen consumers’ abilities to find “sausage making” information. Perhaps the valuable metals used to make the inside of the monitor cause conflict in Africa, or the factories that make the monitor may contribute to coal pollution. While the blackboxing of supply chains makes it much easier for us to act as consumers, not knowing what’s really inside also separates us from the social and environmental impact that our consumer decisions have. Especially the physical environmental effects – while I know that the monitor is Energy Star certified, I don’t often think about the environmental impact about the truck that delivered the monitor to me, the ship that brought it from China, the energy used by the factory, or the environmental harm by mining the metals and making the plastics for the monitor.

Back to what Samsung did show me on their website, the Energy Star and EPEAT certificates, is a way of unblackboxing these supply chains to some extent – various certification programs by 3rd party groups provide a window into the manufacturing and business practices. It is not directly sharing the information, but rather I have to trust their judgement and rating process to get an aggregate rating – a system that still blackboxes much of the actual realities of the supply chain. Though it is still not the same as having all the information, it is a positive step for consumers’ ability to make more informed decisions by knowing more about how the products they buy get made.